Reading and the Cerebellum

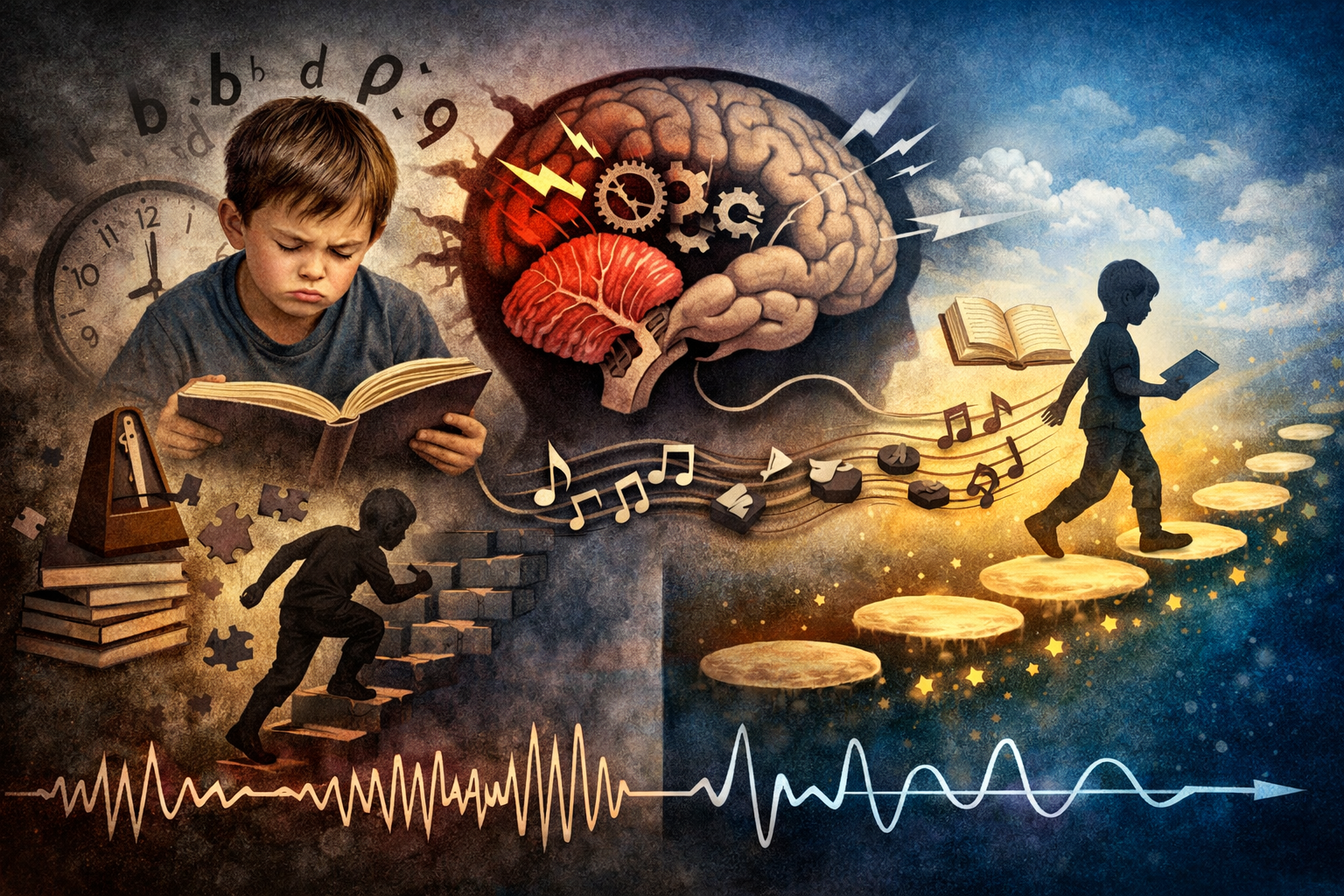

Reading is such a complicated topic. On the one hand, it seems straightforward beginning with letter identification, phonics, and spelling. But if we step back and look at the procedural skills necessary for the automatization of these skills, we see that there is nothing straightforward about reading.

Reading is not strictly a cortical language task. It is a procedural and automatized skill with rhythm and timing components. The cerebellum plays a central role in fluency, sustainability, and efficiency of reading skills.

For our children with Down syndrome, the cerebellum sits at the crux of the issue, as it is the center that regulates sensory information coming in for focus and attention, regulation for full access to the thinking brain, and the center for procedural learning.

The cerebellum in our children is physically, structurally, and chemically different in dozens of ways. It is no surprise that typical phonics-based “learn to read” programs are not always effective for our children.

What Does This Article Intend to Do?

It is my intention to briefly overview three bodies of work. Two were groundbreaking (and often dismissed) in the 1950s–1970s, and one is a modern-day researcher who, through the use of modern imaging, has developed theories that substantiate the earlier work.

All of this work centers around the cerebellum as the main component in fluent reading and comprehension. And, as if you have never heard me say it before, our children with Down syndrome have dozens of significant differences in their cerebellar structure, function, and chemistry. This is why programs that are cortically and hemispherically based are helpful only to a degree for our children.

The end of this paper is a literal brainstorm of what we might see as a cerebellar-based reading program. What are the components? How might it look?

I must state clearly that this is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be therapeutic or educational advice. You should never start a new program without first discussing it with your child’s physician, therapy, or school teams when appropriate.

Ok. Ready?

The Original Systems Thinker

Carl Delacato was a speech-language pathologist who famously rounded out the trio of Doman, Delacato, and Temple Fay in the 1950s and 1960s. His radical core assertion was that reading and language problems were not academic failures; rather, they were failures of neurological organization.

Delacato’s hypothesis was that brain organization follows a predictable developmental sequence and that each level builds upon the last. Skipping stages equals consequences. Decades before fMRI and modern understanding of neurocognition, Delacato understood that if earlier stages are incomplete, higher skills collapse under load.

Delacato argued that reading requires:

• Integrated sensory input

• Organized motor output

• Stable laterality

• Efficient cross-hemispheric communication

If these are not fully established, reading becomes labored, fluency never emerges, and comprehension drains cognitive resources. (We now understand this is because the cerebellum is not automatizing what must be automatic. This is procedural learning decades before we had the term.

One of Delacato’s most important claims is that children who do not crawl properly are at risk for reading difficulties. Crawling builds bilateral integration. This is one reason why crawling is not just a milestone to be achieved, but a method for integration. It establishes hemispheric dominance, organized hand–eye control, and trains timing and sequencing. Basically, crawling is the cerebellum’s calibrator.

Delacato also believed that sensory disorganization was intricately linked to difficulties with academic learning. Issues with auditory processing, visual tracking and convergence, and poor body awareness are processes of neurological organization. Delacato understood that instead of academic-based reading intervention, the focus should be on targeted neurological patterning, repetition of developmental movements, and sensory-motor inputs delivered with frequency and intensity.

Delacato and his groundbreaking work were dismissed because he was several decades too soon. His hypotheses were unbelievable until the creation of functional imaging validated much of his work.

Sensory Integration and the Diagnosis of Exclusion — Down Syndrome

A. Jean Ayres, occupational therapist and neuroscientist, developed her groundbreaking work on Sensory Integration Theory. Although the theory itself is important insofar as all sensory input and integration are responsible for the outputs of the brain, she makes it perfectly clear that it does not answer questions related to individuals with Down syndrome.

In Sensory Integration Theory and Practice, Third Edition, page 16, it clearly states:

“Sensory integrative dysfunction is a diagnosis of exclusion. That is, it is used to explain dysfunction in motor planning or sensory modulation that cannot be explained by frank CNS damage, genetic issues, or other diagnostic conditions.

Children with a range of developmental disorders may have deficits in functions typically associated with sensory integrative dysfunction. However, SI theory is not intended to explain, for example, low muscle tone, poor proximal stability, or poor equilibrium experienced by children with Down syndrome…

Their problems are more clearly attributed to abnormalities of the cerebellum (Nommensen & Maas, 1993)….”

She explicitly states that:

• hypotonia

• postrotary nystagmus differences

• equilibrium problems

• proximal instability

in children with Down syndrome are not explained by SI theory.

This is a major reason why programs, whether reading or otherwise, that are based in sensory integration practices work well for other diagnoses but not completely for our children with Down syndrome. Our children have distinct and unique cerebellar disturbances physically, structurally, and chemically as early as the second trimester in utero.

Procedural Learning and the Cerebellar Deficit Hypothesis

Fast forward several decades, and the foundational framework for the Cerebellar Deficit Hypothesis (CDH) was developed by Professor Rod Nicolson and Angela Fawcett. It proposes that many reading difficulties, especially those with a dyslexic pattern, stem from impaired cerebellar contribution to the automatization of skills.

The cerebellum:

• builds internal models (praxis)

• regulates timing and sequencing

• reduces the toll on conscious effort

• allows skills to be durable and generalizable

When cerebellar function is compromised, skills remain effortful. Think of what it would be like to have to think about every single step of driving a car like the first time you tried. The process never automated. Every time is the first drive. That is what happens for our children who are using conscious effort to learn.

When we rely on conscious, mechanized declarative learning, performance collapses under load. Learning does not generalize. And although our children are amazing at declarative learning, procedural learning never fully develops.

Nicolson reframes reading as a procedural skill, not a purely linguistic one.

Reading requires:

• rapid eye movement control and teaming/convergence

• temporal sequencing (the brain’s ability to organize, time, and execute events in the correct order with appropriate speed and rhythm). This is different from pure sequencing, which is order only—first, then, last. This is a cortex-heavy skill that can be taught declaratively. Temporal sequencing is cerebellar: first, then, last at the right speed, time, and rhythm.

• automatized phoneme–grapheme mapping (the brain’s ability to rapidly and unconsciously link written symbols to speech sounds without deliberate decoding). Think Hangman—being able to see the word map without many of the letters. This relies on the cerebellum for timing, prediction, and error correction.

• motor planning (praxis: speech, visual–motor, gross motor, fine motor, ideational motor, etc.)

• coordination across networks

This is why a child can pass every single phonics assessment and still fail to read fluently. The cerebellum is not automatizing the skill.

Why Is It Important to Understand All of This?

Phonics instruction alone is insufficient for children with Down syndrome. Repetition without an integrated foundation will not stick. Phonics models explain how reading is learned. Cerebellar-based models explain how reading becomes fluent.

When we use a phonics-only curriculum to teach reading, it assumes that reading is a language-based skill, that fluency will eventually follow repetitive practice, and that the cortex is the main driver. We proceed under the assumption that repetition makes perfect. To what, then, do we attribute the number of teens with DS sitting in special education classrooms working on basic reading words or letter/phonics work?

Repetition-based phonics targets the cortex. It is insufficient for individuals with dozens of cerebellar differences.

With the addition of a cerebellar-based model, reading is procedural and requires automatization. Knowing rules, blends, and sounds does not equal fluency.

Six Core Pillars of a Cerebellar-Based Reading Program

1. Regulation Comes First

The cerebellum will not automatize under sympathetic dominance. When dysregulation takes hold, our children tend to hold their breath, experience postural collapse (think head down on an arm while trying to read), and exhaustion due to excessive cognitive demand.

How can we influence this?

• breathwork (e.g., box breathing)

• supported posture

• predictability

• low emotional “threat”

This is why “trying harder” kills fluency. It introduces stress, and stress unwinds the system.

2. Rhythm Before Symbols

We are not talking about music class. We are recognizing that the cerebellum is fundamentally a timing organ.

How can we influence this?

• rhythmic clapping

• alternating bilateral tapping

• metronome work

• call-and-response vocal rhythm (if able)

3. Temporal Sequencing Without Language

Before phonics, the nervous system must be able to integrate ordered timing.

How can we influence this?

• sound…pause…sound

• movement…stop…movement

• visual cue…motor response (keeping in mind motor praxis is an outcome of cerebellar integration)

This builds anticipation and prediction.

4. Eye–Hand–Voice Integration

Reading fluency is about syncing eyes with motor output and vocal output. This is where life becomes very hard for our children in their quest to become fluent readers with comprehension. Each individual praxis loop for eyes, gross motor, and voice, can be affected by the cerebellum.

Training can include:

• paced visual tracking

• matching vocalization to an external rhythm

• using hand movement to set timing

The cerebellum learns through coordinated loops. Improve one, improve the others.

5. Phoneme–Grapheme Mapping After Rhythm and Timing Are Established

This is where we use phonics.

Phonics should be:

• rhythmical

• predictable

• repeatable

6. Fluency Is Trained Directly

• repeated reading with timing/rhythm support

• pacing tools (e.g., metronome)

• short duration, stopping before the individual wants to

• always end with success. Always

The cerebellum learns best when it finishes successfully. This is another reason why pushing on and going longer is counterintuitive.

The Big Picture

Phase 1: Timing & Regulation

• rhythm

• bilateral movement

• breath and posture

• sequencing without symbols

Phase 2: Symbol Timing

• letters introduced rhythmically

• phonemes paced externally

• eye–voice coordination

Phase 3: Guided Automatization

• supported fluency

• short text

• pacing maintained

• minimal cognitive demand

Phase 4: Generalization

• gradual removal of supports

• increase variability, not speed

• protect fluency under load

Reading is not simply a language-based, cortical skill that becomes fluent through repetition; it is a procedural, timing-dependent skill that relies heavily on cerebellar function. While phonics instruction explains how reading is learned, it does not explain how reading becomes fluent, sustainable, or efficient, especially for individuals with Down syndrome, whose cerebellum is structurally, chemically, and functionally different from early development.

Decades of work, beginning with Delacato’s early systems-level observations, clarified by Ayres’ explicit exclusion of Down syndrome from sensory integration explanations, and later mechanized by Nicolson’s Cerebellar Deficit Hypothesis, point to the same conclusion: when the cerebellum cannot effectively support timing, sequencing, and automatization, reading remains effortful regardless of instruction quality.

A cerebellar-based model of reading reframes fluency as a neurological outcome and demands that intervention prioritize regulation, rhythm, temporal sequencing, and procedural learning before expecting automatic decoding and comprehension to emerge.