Hip Dysplasia; Beyond Musculoskeletal Concerns in Individuals with DS

Hip dysplasia is when the ball and socket of the hip joint don’t fit together properly and is more common in our children than in the general population. What makes it tricky is that it doesn’t always show up at birth. In fact, many children with DS pass their newborn screenings and well baby checks just fine, only for hip issues to appear later in childhood, sometimes even during the teenage years. And to complicate matters, our children often don’t reliably report pain, which means things can progress silently until walking or movement is noticeably affected.

Why Hips are Vulnerable in DS

Our children’s bodies are beautifully unique, but they come with a few challenges that place extra stress on the hips:

- Hypotonia (low muscle tone): Muscles may not hold the joints together securely.

- Ligamentous laxity (loose connective tissue): The ligaments meant to stabilize the joint stretch more than they should.

- Without the joint being held together compactly and appropriate tension in the tension, the critical sense of proprioception (knowing where our limbs are positioned and understanding the forces acting on them) is inhibited.

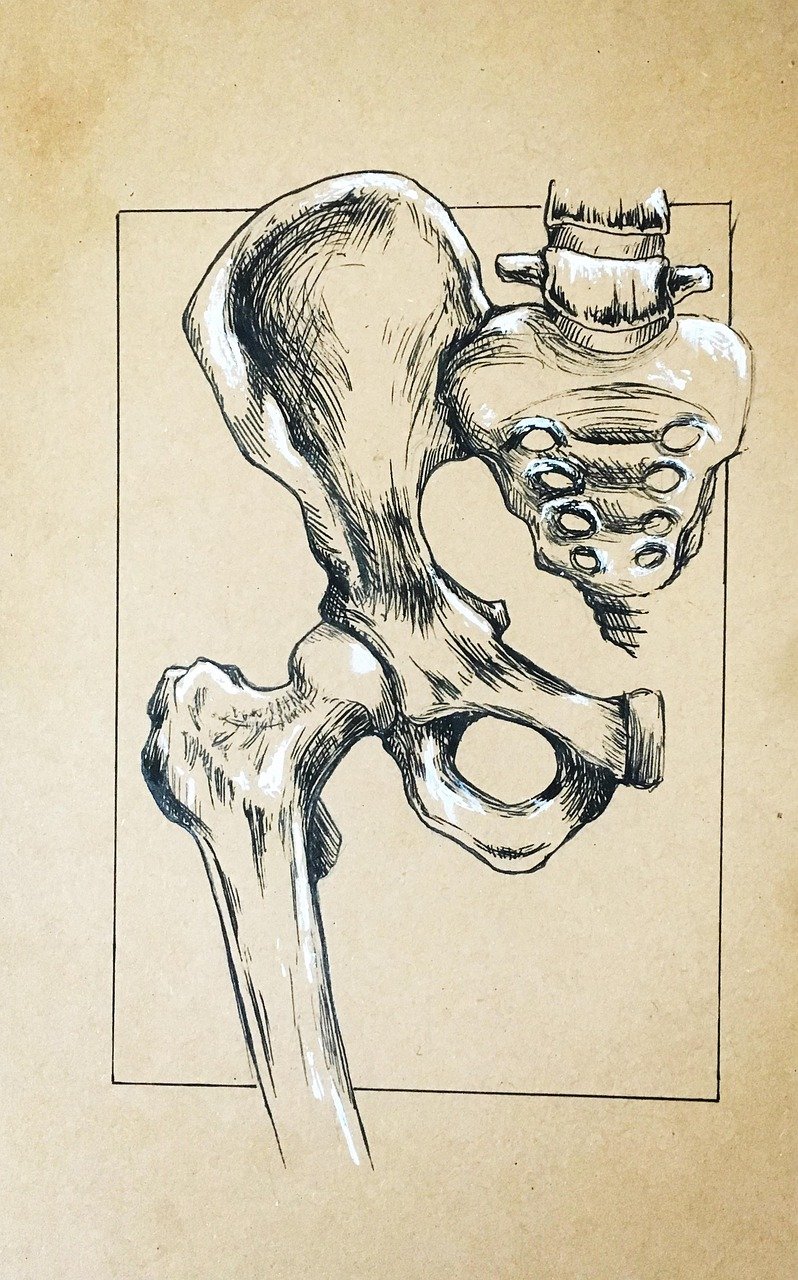

- Bone shape differences: Research shows that the acetabulum (hip socket) in DS is often shallow, insufficient in multiple directions, and rotated backward.

When you put those musculoskeletal considerations together, the hip doesn’t always get the pressure and contact it needs during crawling, standing, and walking to grow into a deep, stable socket. Instead, it starts to slip upward and outward, slowly working toward subluxation or dislocation.

Beyond Biomechanics: The Brain–Body Connection

As with so many other components to out children’s overall development, hip dysplasia is not just about bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

The cerebellum, which is underdeveloped in DS, plays a huge role in balance, timing, and automatic movement. If the cerebellum isn’t firing in sync with the vestibular system (our inner ear balance mechanism) and proprioception (our sense of joint position), our kids adopt wider stances, shift weight unevenly, and vary step timing. All of this impacts how hips bear weight.

For a child who isn’t yet walking, difficulties with the cerebellum integrating the sensory system , primitive reflexes, and postural control, lead to our children moving in various ways that further strain the hips. A prime example is getting in and out of sit through “the splits.”

Interventions that strengthen vestibular and proprioceptive inputs like swinging, gentle spinning, standing on uneven surfaces, and rhythmic walking practice, have been shown to improve balance in kids with DS. That means the right kinds of sensory-motor play along with proper developmental sequencing transitions can actually change how the hips are loaded during movement, protecting them long-term.

Folate, Methylation, and Connective Tissue

Another consideration is less obvious but worth mentioning. Folate and the body’s methylation cycle (something many of our kids struggle with) are connected to bone health and connective tissue integrity. Research has suggested a link between folate metabolism and joint hypermobility.

Testing to uncover genetic mutations and creating a plan unique to your child’s biochemistry to optimize methylation is a good step to take, not just for joint and connective tissue reasons, but for numerous biochemical reactions that influence health, development, and learning.

What Families Can Do

The following are some steps you can take to protect the hips and encourage proper movement patterns. Given that our children may be unreliably indicated discomfort or pain, it is critical that you check with their doctor and obtain an assessment if you have concerns.

In infancy and toddlerhood:

• Swaddle loosely allowing the legs to naturally be together during rest or carry.

• Stitch the legs of snug sleepers together so little legs don’t flop into extreme abduction or external rotation during sleep. You can also try the wedge positioners to keep legs in a neutral position.

• Avoid carriers that widely spread legs apart and rotate toes outward. If using a carrier or stroller, use rolled towels alongside the thighs to keep legs in a neutral position.

• Encourage time on the floor, creeping / crawling, and movement that keeps hips flexed and abducted.

Life on the floor:

• Give as much time as possible for play and movement on the floor, this is where hips develop best.

• Insist on proper transitions. Don’t rush milestones. In the routine transitions between positions is where integration happens. It may take longer for our children to begin moving in the proper way, but it is very important.

• Avoid “the splits” posture, where hips fall out to the sides. Encourage play in side-sit and certainly encourage crossing midline while bearing weight on uppers and lowers.

As kids grow:

• Build balance through vestibular play such as swings, balance boards, and completing proper developmental sequencing on challenging surfaces such as trasitioning sit to quadruped on a balance board, etc.

• Strengthen hip and core muscles with supported squats, step-ups, side steps, bridges, and carrying activities.

• Use rhythmic walking, lateral stepping with bands (With approval from therapist or doctor), or compliant surfaces (like foam mats) to activate hip stabilizers and cerebellar timing.

• Consider tools like Hip Helpers shorts (with the guidance of your doctor or therapist) to help keep legs in safe ranges during play.

Neurodevelopmental considerations:

• Evaluate and address primitive reflexes (like ATNR, STNR, and TLR) that, when retained, can block proper hip movement and posture. Working through reflex integration allows mature postural reflexes to develop, setting a stronger foundation for hip stability and efficient movement.

For all ages:

• Ask for a yearly hip exam. Even if the newborn screen was normal, late-onset hip problems in DS are well-documented.

• Request an X-ray if you see a limp, reduced hip range of motion, uneven leg length, or changes in gait. Don’t wait for pain to appear.

The Big Picture

Hip dysplasia in Down syndrome isn’t just a musculoskeletal problem, it’s a whole-system issue that touches muscle tone, connective tissue biology, brain–body integration, and even nutrition. When we take all of that into account, we see more opportunities for intervention.

The following is a list of references for further study.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2022). Health supervision for children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Pediatrics, 149(5), e2022057010. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-057010

Bauer, J. M., & Song, K. M. (2019). Pediatric hip dysplasia: Diagnosis and management. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 50(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2019.06.001

Beals, R. K., & Robbins, J. R. (1991). Hip instability in patients with Down syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 11(6), 677–682. https://doi.org/10.1097/01241398-199111000-00002

Bischof, J. M., et al. (2014). Developmental dysplasia of the hip in children with Down syndrome. Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics, 8(6), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-014-0631-0

Galli, M., Rigoldi, C., Mainardi, L., Tenore, N., Onorati, P., & Albertini, G. (2008). Postural control in patients with Down syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(17), 1274–1278. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701610353

Ghai, S. (2019). Effects of rhythmic auditory cueing in gait rehabilitation for children with Down syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00117

International Hip Dysplasia Institute. (n.d.). Hip-healthy swaddling. https://hipdysplasia.org/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip/hip-healthy-swaddling/

Khasawneh, R. R., et al. (2020). Vestibular stimulation improves balance in children with Down syndrome. NeuroRehabilitation, 46(4), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-193004

Liu, Y., et al. (2015). MTHFR polymorphisms and bone mineral density: A meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International, 26(4), 1221–1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2992-4

McKeown, C., & Wylie, R. (2021). Folate and methylation in connective tissue health: A review of evidence and hypothesis for hypermobility syndromes. Medical Hypotheses, 147, 110503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110503